Lean Thinking and Traditional Manufacturing

Lean thinking is a process focused on increasing the value added to products and services and the reduction of waste. The term “lean,” coined by James Womack during one of his visits to the Japanese carmaker Toyota in the early 1980’s, has become the universally accepted term for increasing value and reducing waste. When talking about value, we refer to everything undertaken with a product or a service for which customers are willing to pay additional.

Waste, conversely, refers to all activities that do not add value from the customer point of view, i.e. everything for which customers are not willing to pay extra. Examples of added value for manufacturers include extra product features deemed valuable by customers, shorter lead times, or more convenient deliveries in smaller batches. On the contrary, activities such as keeping excessive inventories, unnecessary transportation, waiting times, or reprocessing are considered waste. For a service organization, common sources of wastes are, for example, long customers waiting times, reprocessing of applications, incorrect automatic charges, or excessive paperwork. In general, there are seven types of waste present in processes.

Overproduction: When more articles than required in a production order are produced. This causes an increase in finished inventory and in holding costs.

Waiting: Idle equipment or operators waiting for raw materials, tools, or maintenance crew.

Unnecessary Transportation: Avoidable transportation of goods, parts, or information is waste. Besides, mechanical damage can be inflicted to parts or goods while being transported.

Overprocessing or incorrect processing: If project orders or processes are not clearly defined, tasks will be performed in the wrong way producing the wrong outputs. This will add more cost to the product or service and customers will not obtain what they are paying for.

Excess inventories: Excess raw material, work in process (WIP), and finished goods inventories produce long waiting times, obsolescence, damaged products, unnecessary transportation, and holding and production costs. Also, excess inventory is related to unlevel demand, supplier problems, defects, long set-up times, and maintenance problems.

Unnecessary Movement: Any unnecessary movements by employees such as to talk to supervisors, search for parts or tools, or excessive walking distances are wasteful.

Defective products: Manufacturing products that do not meet customer specifications is a waste that creates unhappy customers and increases total manufacturing cost.

Recently, an eight waste is often listed together with the seven previous ones (Liker 2004):

Unused employee creativity: Not listening to employees, losing time, ideas, skills, potential improvements, and learning opportunities.

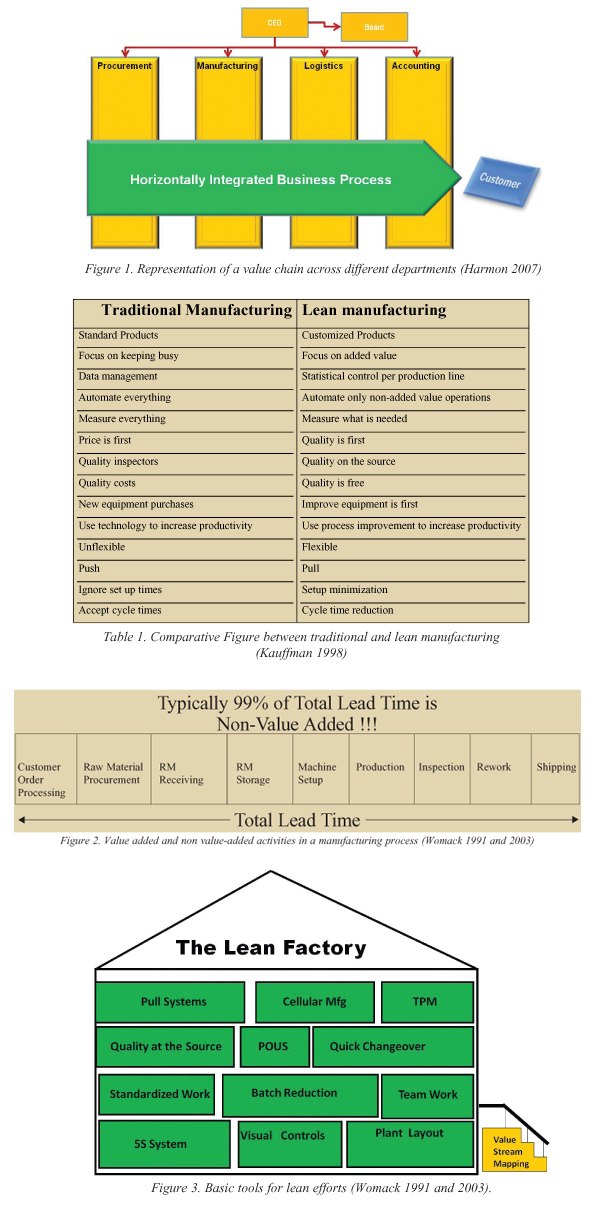

At the core of lean thinking practices is the concept of value chains. Value chains are defined by end consumers through their assignment of values to product or service features. Organizations process raw materials or data to generate goods and services that end customers demand. For this purpose, organizations employ a value chain that integrates different functions / departments. Identifying the value chain is dependent on the level of detail, the resources, and the administrative support available. Ultimately, the level of detail is given by the purpose of the value chain analysis, e.g., to eliminate wastes in the chain to increase effectiveness and efficiency of the organization. Figure 1 shows how a value chain can be defined across multiple departments.

The value chain concept focuses our attention on all processes needed to manufacture or produce a good or a service. Each step in this process is considered as an individual piece of the chain. Sometimes, identifying the value chain is not straightforward. Managers need to understand that the pieces of the value chain that do not generate value from the customer point of view are considered waste or cost.

The relationships between processes, value chains, and costs are fundamental to understand why lean thinking helps to increase our competitiveness. Traditionally, process improvement methodologies have focused on isolated processes without a holistic view. Thus, individual processes were made highly efficient and effective but the value chain remained the same. Although there might be significant opportunities for improvement at each individual process step, the impact on the value chain may be nil. Achieving process improvements (e.g., reducing wastes) for maximum value chain efficiency and effectiveness is the goal, not individual process improvements per se. Indeed, pursuing lean manufacturing requires a different set of approaches than traditional manufacturing does. Table 1 contrasts traditional and lean manufacturing systems.

As shown in Table 1, lean manufacturing requires a different mindset than does traditional manufacturing. Lean thinking focuses on eliminating waste to increase customer satisfaction. Thus, lean thinking will have a positive impact on the financial health of a business. Also, lean thinking discards the traditional pricing formula which states that Price=Cost+Profit. Lean thinking focuses on increasing the value to better serve customers and, at the same time, eliminate wastes to increase profits. Under the lean thinking approach, the pricing formula is reformulated to Profit=Price-Cost, i.e., the only way to increase profits is by reducing wastes or costs.

The Lean Thinking Process

Lean thinking initiatives require complete commitment from the organization’s leadership. If such a commitment is not made, an organization is better served to continue going after their business in traditional ways and to involve alternative process improvement initiatives. Companies having the necessary leadership commitment need to have formulated, agreed on, and worked on implementing their strategic elements – mission statement, vision statement, strategic goal formulation, and action plans. Once these elements are in place, an assessment can be made as to whether the lean thinking philosophy is the appropriate improvement process to use. If lean thinking proves to be the appropriate philosophy, four concepts need to be embraced: value, flow, pull, and continuous improvement.

Value: The critical starting point for lean thinking is value (Womack and Jones 2003). Value has to be defined before analyses can start. A customer buying a product or service signals that she receives the value desired at a reasonable price. Thus, end customers define value. However, when investigating the typical production sequence of a product, as displayed in Figure 2, one realizes that the whole process has few steps that add value for the consumer.

All activities shown in Figure 2 with the exception of “Production” are considered not value-added for the consumer’s perspective. For the consumer, only the sequence “Production” matters, as he does not care about the other steps, such as “Order Placement,” “Raw Material Purchasing,” “Raw Material Reception,” “Raw Material Storage,” “Machine Setup,” “Inspection,” “Rework,” and “Shipping.” All these activities represent waiting, inspections, reworks, or transportations that are not relevant and add no value from the customer point of view. While some of these activities cannot be eliminated (these processes are referred to as necessary, non-value added processes), lean thinkers strive to minimize them as much as possible. In general, in a manufacturing organization, 99 percent of the total product lead time is typically non valued added (Figure 2).

Flow: The focus of lean projects is to eliminate all non value-added activities from the process and to focus on value-added activities from the customers’ point of view. Value stream maps (VSM), a graphic tool to analyze the entire process and identify processes that add value and those that don’t add value are used for this purpose. Once the value-added processes are identified through value stream mapping, the challenge is to achieve smooth flow among the remaining process steps.

Flow is limited by the organizational structure and the way raw material and data is processed to produce value in each operation. For example, traditional organizations are structured by departments or functions, thus disconnecting departments. Raw material and data is processed in batches, requiring the next process to wait until the whole batch has arrived. Thus, flow is impossible to achieve if the organization does not change structure to a process oriented form and reduces batch sizes.

Identifying value chains is challenging. In manufacturing environments, the core process is to produce a particular good. Other processes needed but not necessarily adding value, might include: sales, order generation, purchasing, engineering, scheduling, delivery, and customer support. Thus, a value chain is composed of different processes across many departments or functions. Also a series of auxiliary processes support the core process (these processes are typically called secondary or support processes). Secondary processes in our example might include: information systems, accounting, marketing, human resources, and procurement. Creating flow among all these primary and secondary processes is challenging and requires a critical look at an organization’s structure and organization.

Pull: Inventory control in traditional manufacturing is used to purchase, and stock the correct quantity of raw materials. Information used for making these decisions is mostly based on forecasts that rely on historical data. Since such history-based systems result in under- or overstocking, the factory always ends up with too much or too little material and a finished good inventory with too little or too much goods.

Raw material gets pushed into the production process thus becoming Work in Process Inventory (WIP), and processed material gets pushed into the finished goods warehouse. Money and other resources are tied up in these inventories and affect the financial health of the company. At the end of an accounting period, products get pushed to the wholesalers and retailers to make the quarterly numbers, creating inventory problems at your partners’ sites.

A lean manufacturing system changes the mode of operation from push to pull. Raw material is only received, converted into a product, and stocked in the finished goods warehouse if a product is sold. Thus, no excess inventory accumulates and products flow smoothly through the process of receiving orders, and producing and delivering goods.

Continuous Improvement: Since the ideal state described above concerning value, flow, and pull is never reached, continuous improvement is the tool to continuously improve operations to deliver better value to customers and to achieve better financial performance. Thus, efforts to eliminate non-value added activities, to achieve flow, and to pull production will never be entirely successful, making our strive for perfection a never-ending, continuous undertaking.

For this end, lean practitioners have a large set of “tools” that they employ in their effort to improve. Figure 3 displays some of these systems.

A perfect process creates value for the customer and does not cause waste. Also, the process has to be capable, meaning that the process is under control and consistently delivers the output expected with minimum variability. Furthermore, the process has to be adequate, meaning that it has the right capacity and the process needs to be available, meaning that the process is available to perform its function when needed.

Creating and maintaining a “perfect” process is a continuous effort, and we always fall short. Fortunately, there are “tools” that can help us reach the perfect process or the perfect value chain. These “tools” are considered fundamental blocks of lean efforts and are shown in Figure 3. These “tools” can be used alone or in combination to eliminate waste, increase value-added, eliminate or reduce variability (capability), increase process availability (flow) and to level demand (adequacy). The following sections explain how to use these tools to strive for perfection.

In the next article we will introduce the fundamental blocks of lean. Stay tuned!

Dr. Henry Quesada is an assistant professor at Virginia Tech specializing in the area of business management processes and modern manufacturing systems. He works primarily with the forest products industry. If you have any questions please feel free to contact Henry Quesada at quesada@vt.edu. Dr. Urs Buehlmann is an associate professor at Virginia Tech focusing on manufacturing systems, engineering, business competitiveness and globalization.